In Hamtramck, a beautiful piece of history is saved

My latest at AlterNet.

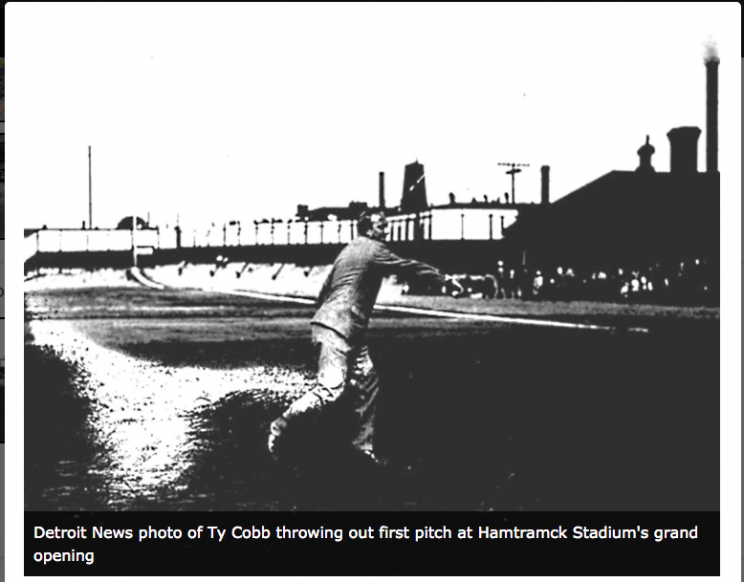

Hamtramck Stadium is one of the last still-standing Negro League baseball fields in the country. Built in 1930, it was home field to the Detroit Stars. Some of the greatest baseball players of all time played on its field, including Cool Papa Bell, Smokey Joe Williams, Willie Wells, and Detroit’s own Norman “Turkey” Stearnes. Seventeen Hall of Famers played there. And in 1930, it was the site of what is most likely the first African American economic protest in the state of Michigan.

As a result of this rich history, Hamtramck Stadium is cherished by baseball and civil rights fans alike. The pitcher’s mound is still here, and a big portion of the original grandstand still sits, dilapidated, behind home plate. On a recent weekday afternoon, kids from Hamtramck High milled about the mound, taking pictures and basking in the late-November sun.

But what makes this site even more special is that the kids on the field that day were speaking Arabic. Where baseball was once the primary sport, cricket and soccer are now popular. The people coming together to preserve and restore the site reflect a unity across racial, cultural and class lines showing how diversity can grow from a segregationist past.

Hamtramck is a small city within the city of Detroit, incorporated in 1922 to keep the rapidly expanding Motor City from subsuming it. At the time, the population was predominantly Polish, with an African American minority. Most of the adults worked at the Dodge Main plant, cranking out 140,000 cars a year.

Today, the Dodge plant is gone. People of Polish descent make up just 12% of the population. Yemeni make up nearly a quarter of the city’s 22,000 residents, and nearly 20% of the population is African American. As much as 19% are Bangladeshi. There are also people from Bosnia and Ukraine, and religious groups ranging from Muslim and Hindu to Catholic and Buddhist. Hamtramck has the highest population of immigrants in the state of Michigan, at 44%. The poverty rate is nearly 50%.

The city council is predominantly Muslim, albeit culturally diverse, and the town occasionally makes the news as a result. Among the town residents, people seem more concerned with whether or not their neighbor is caring for their yard or cleaning up their dog’s poop from the sidewalk than anything else. As one café patron told me, separation of church and state is the law in this country. Why would it be any different here?

Adam Mused, 35, is a Hamtramck native, the son of a Yemeni father and a Mexican mother. He works at Hamtramck High School as head varsity baseball coach.

“I used to play on that diamond growing up,” he says of Hamtramck Stadium, adding that he and his colleagues take pride in the history of the stadium. “We teach [the students] baseball, but also the history of the people who have been there before them.” That includes the 1959 Little League World Series winning team, and their pitcher, Art “Pinky” Deras, known as the greatest Little Leaguer to play the game.

“There’s a lot of baseball history here,” Mused says. “Because so many demographics move in, it means the people who do care about it have to work to keep it alive. It speaks to change, but it doesn’t have to speak to us losing something because people aren’t familiar with it.”

Nearly 100 years ago, segregation was a very real institution in the United States. Yet at first, baseball was integrated, says Gary Gillette, a writer of well-worn baseball encyclopedias and a former ESPN contributor. He’s also founder and president of Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium. Gillette says that back in the 19th century, black players played with whites, including two black brothers who played for Toledo. However, by the 1890s, the color line became rigid.

So, African Americans simply created their own baseball teams and leagues, with many players of major league quality. For years, these professionals played in Negro League parks across the country. Black papers reported on the games, players and teams; black-owned businesses supported the sport; and it was the thing to do on a Sunday afternoon.

These all-black entities gave the community economic power. According to Gillette, the owner of Detroit Stars from 1925-1931 was a white man named John Roesink. He hired whites to sell the tickets and work the concessions—the “good” jobs—and hired blacks to pick up the trash. This infuriated black community members, who effectively boycotted the Stars. The boycott nearly bankrupted the team, and it forced Roesink to apologize, hire blacks at the park and turn over club management to a black man. This was, quite possibly, the first economic civil rights boycott in the state of Michigan, in 1930.

“That was a sacred ground for developing stellar ball players back then, for development purposes as well as for economic purposes,” says local coach Michael Wilson. “It was an economic lifeline for the community, and it created jobs. Groundskeepers, concessions, tickets, paying the players… It’s a long-term goal to generate revenue for the community as a whole, and develop young people growing up in that area.”

Coach Wilson was born in Hamtramck. His father played in the Negro League for the Chicago American Giants. He moved to Detroit after his career ended, and became a coach. The younger Wilson was drafted by the Tigers, and played minor league ball. Today, the younger Wilson has followed his dad’s footsteps and become a coach, as well as vice president of the Friends for Historic Hamtramck Stadium.

“This is something that was the hallmark of the African American community in the ’20s and ’30s, and it meant a lot to people of African American descent,” says Wilson. “I’m passionate about it because I recall when it had tremendous status in the community. There were some incredible players that came out of that… It’s really near and dear to me.”

The Detroit Stars stopped playing at field in 1937. And then in 1947, Jackie Robinson re-integrated baseball, and by about 1950, major league teams were scooping up young Negro League stars. The older Negro League players—over the age of 30, that is—continued to play in the Negro League into the 1960s. By then, many of the black newspapers were gone, as were the black-owned businesses that supported them—one of the side effects of integration.

The stadium itself was renovated twice: once in 1941 with WPA money, and again in the 1970s, when the city took over maintenance. It seated 9,000 to 10,000 in its day, depending on ticket sales and how tightly people would pack in to catch a game. Now, about 2,000 could technically fit into the bleachers, if they were restored.

Hamtramck Stadium was put on the National Register of Historic Places in 2012, and the Friends of Historic Hamtramck Stadium is working to raise money to renovate and restore the field for public use—high school games and official games in youth sports, including baseball, football, soccer, and cricket. Their goal is to make it available for the community, concerts, 4th of July parties, and summertime movies.

“If we’re gonna raise money to renovate it, we want it to be a community resource,” says Gillette. “We want it used as much as possible, by as many different groups as possible. The dominant will be soccer and cricket, ’cause that’s what the kids play. Our goal is to make it accessible to all people.”

In addition, “We want to be able to establish a museum on the grounds to pay tribute to the Negro League players who played there,” Wilson says. “It’s been a hidden jewel for too long.”

Until then, the official keeper of the field is the Navin Field Grounds Crew. This was the group responsible for taking over the former site of Tiger Stadium, and unofficially rehabilitating it into a park for everyone in the community. Unfortunately, the city gave away the lot to a developer, who just laid astroturf on the sacred ground last week. While that continues to be a painful loss for Detroiters and baseball fans alike, the Navin Field Grounds Crew and their intrepid leader Tom Derry see what appears to be a permanent community effort to preserve Hamtramck Stadium. At the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, where Tiger Stadium once stood, they just did what they thought was right. The city of Hamtramck saw that, and invited them to come and do the same thing at Hamtramck Stadium, officially.

“We’re happy to be a part of this new project,” says Derry. “This year, we’ve been cutting the grass and picking up trash. We’re hoping to work on the pitcher’s mound and do some things with the infield. This is a work in process, but we plan to be there for the long term.”

Derry is excited about the project, not just the historical significance of the site or the 17 members of the Hall of Fame, but by its use by the residents: “We see them using the field, playing soccer, baseball, cricket, or just walking or having a picnic. They’re using the site, and we’re excited to be a part of that.”

Derry says the grounds crew will work through the winter, picking up trash and making sure the park is clean. He’s planning one final grass-cutting the first Sunday of December, when it’s supposed to be an unseasonably warm 50 degrees. “We love the game of baseball and we love to give back to the community.”

“Many of the greatest players of all time played here,” says Derry. “Satchel Paige, Cool Papa Bell, Turkey Stearnes… We’re into baseball and the history of the game, and we realize the history of the site and how important it is to restore it. It’s a real gem, and it’s so cool that it’s gonna be restored, and we’re gonna be a part of it.”

Learn more about the efforts to save Hamtramck Stadium.

Thank you for reading this story. If you were moved by it, please consider sharing it with your networks and making a gift in support of my work.

Thank you.

You must be logged in to post a comment.